You have practiced countless hours, you know your scale positions and fingerings like the back of your hand, you can play faster than all your friends. Yet, all the solos you improvise (or write) sound kind of stale, and not like "real music". Why? Years ago when I was a beginner this problem was driving me crazy. How comes that some people can play just three notes and make them sound like music, while other simply can't, no matter how much or how little they play? I found out that there are many possible things that can go wrong while trying to play melodically. I compiled a list of the most common reasons that prevent your improvisations to sound like music, adding some tips on how to overcome them.

Some of the points that I will be making here are of purely technical nature, while others are on the emotional side of things. A good solo (like all music) is an expression of the player's emotions. Music is a synthesis of technique and art, and in order to be a good musician you need to have something to express (emotion) and the means to express it (technique. We will start from the technical issues and then we will gradually move to the emotional ones.

The first reason is probably the most common among guitarists (and drummers). Playing too many notes is the defining characteristic of "the obnoxious guitar player" that other musicians, not to mention the public, dread so much.

It is important to realize that the term "overplaying" has a relative meaning. Some songs may require a slow solo, while others will call for a solo with a lot of notes and fast runs. Not all fast guitarists are automatically guilty of overplaying. A shred solo does require lots of notes, and if the song is composed so that it sets up the solo properly then even the fastest solo can't be considered overplaying. It is a matter of context and taste.

The solution here is ridiculously simple: just play fewer notes! Train yourself to improvise over a backing track using only 1-2 notes per bar. If the backing track is in 4/4, this means one note every 2-4 beats. It seems easy, but if you try it in practice you will discover that you have to resist the urge to speed up. Do not give up!

1. When overplaying the superfluous notes obscure the melody line. Actually some people play too many notes trying to hide the lack of melody in their solos!

2. It is not very important how fast you can play, but how much is the difference between the slowest and the fastest note you can play. If you can give a lot of contrast between slow and fast passages, the fast passages will seem faster.

3. It is generally a good idea to keep your fastest licks for the end of your solo/improvisation. If you play them too soon you will have nothing else to entertain the listener afterward.

Now that you have your foot firmly on the brake and not overplaying, you will start to notice that slow notes may not actually sound that good by themselves. If you feel the urge to play fast to hide this, resist it. The problem does not lie in the fact that you are playing slowly: the culprit is your lack of familiarity and training with long notes. Yes, you heard me correctly. Many of us spend lots of practice time in order to play faster (an endeavor that I applaud), but how many of us actually practice to play one good long note?

If you practice with only one note at your disposal you will soon discover that the rules of the game are different. It's not anymore only what you play, but also how you play it (i.e. your phrasing). The two most common problems that guitarists encounter in this respect are 1) bends not in tune and 2) bad vibrato (too fast, too narrow, not regular). If you are doing the exercise I suggested above, i.e. improvising just with few long notes, you may start to notice these issues. If so, that is great! Only if you hear the problems in your playing you can fix them. I will not expand too much on the topic of bends and vibrato here, since it is a topic that requires a lot of space and there are already good articles on the web about that. What I will say here is: set aside some time in your daily practice routine to practice exclusively single notes with bends and vibrato. A good vibrato is the signature of any good player.

Of course, even if how you play it is very important, what you play still retains a certain importance (random notes are not everyone's favorite melody). Even if you are playing in the right key with good phrasing, sometimes your improvisation fails to "glue" to the chord progression in the backing track. This happens because at any given moment in music some notes are more "right" than others. The short story is: the "right" notes are the ones that are included in the chord that is playing in that moment (the so-called "chord tones"). If this last statement is not clear to you, I am going to clarify it in a minute. In the meantime, let me state an important fact: in general you are not restricted to play only "right" notes. In fact, you can play literally whatever you want as long as you stop on a "right" note (this last statement has a lot of exceptions but it's a good starting point). This is the meaning of the often cited quote "there are no wrong notes, only wrong resolutions" attributed to at least 20 different Jazz musicians.

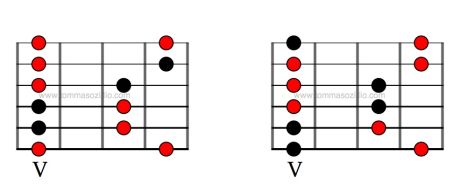

Now, let's clarify this concept: chords are composed by at least three notes. For instance the C major chord is made by the notes C, E, G. So, if the backing track is playing a C major chord on a certain moment, I have to finish my phrases on a C note, or an E note or a G note. If the chord changes, my "target notes" change too. At the beginning this seems hopelessly difficult to manage (after all you have to 1. know what chord is playing right now; 2. remember the notes of this chord; 3. find them on the fretboard; and 4. play them, all at the same time!). With a bit of structured training this becomes very easy. All good players have practiced targeting chord notes until it became second nature. The key to understand it is to use some visual guide, like the following diagrams that show the chord notes for Am and C in the Am pentatonic scale.

Of course, this is just a very short introduction and a complete explanation of this topic would be quite lengthy. I have prepared a free e-book, complete with guided backing tracks, explaining step-by-step this chord tone thing with practical exercises that will let you play effortlessly following this concept in just a little time (if you will follow the exercises, of course!).

As I am fond of saying, music is a team sport. While you can certainly have some fun by yourself, it is not even close to the fun you can have playing with other people (or for other people, as we will see below). With this I do not mean that you have to play only with other guitarists, but also with bass players, drummers, singers, keyboard players, in fact any kind of musicians you can find.

I know what many of you are thinking right now: "But I am still not good enough to play with other people / have a band". Well, let me be blunt here: if you do not go out and play with other people, you may never become good enough! You can't learn how to swim if you do not enter in the water. If you want to learn how to play basketball you can't do it alone. You may not be good enough to enter the NBA yet, but you can surely find someone in your neighborhood that will play with you. The same goes for music.

You will discover very soon that when you are playing with other musicians, the dynamics of your playing is completely different. You have to adapt to what other people are doing, react to their music, and give your own interpretation. Lots of good players have honed their skills by playing in bands, and you should do the same. By the way, this is also one (but not the only) reason to have a good teacher: you will be playing regularly with someone better than you.

One corollary of "music is a team sport" is that when you are playing with other musicians you have to listen (and in general pay attention) to what and how they are playing. How can you tell if you are paying attention to the other musician (or the backing track)?

1. You find yourself looking at your fretboard all the time and not at the other musicians, you are not paying enough attention. Good musicians look at each other all the time.

2. If you start improvising as soon as the backing track/band starts, you are not listening. Good musicians let few bars pass before improvising to absorb the feel, the tempo and the chord changes of the song.

3. If you are just waiting "for your turn to play", you are not listening.

A good way to learn how to listen is called "to trade fours". You need another guitarist to do this. While playing together, for 4 bars you will be playing the rhythm and he will be soloing, for the next 4 bars you will invert the roles and so on. Your task is to play something in context with what he just played, ideally making it seems like there is only one soloist and not two.

Even if you wanted to, you can't play with other musicians all the time. Every good athlete trains with his team but also on his own, and we musicians should do the same. Backing tracks offer a non-interactive simulation of a band that can help you train a quantity of different things. You can play them as many times as you want: they will never be tired of repeating the same thing. On the other hand, backing tracks are less inspirational and less fun than playing with a real band. For that reason backing tracks are not a substitute of playing with other people, yet they can still be useful.

Training with backing tracks should be part of your daily routine, but you should not just blindly improvise over the backing track. You should have in mind a technique or a concept that you want to implement in your playing, such as: "Just few notes with a good vibrato" or "let's try to implement this lick I just learned". Personally, I think backing tracks are incredible for learning the "right" notes to play, as explained above. The problem is that you should know the chord progression of the backing track beforehand to be able to target the chord tones. To solve this problem I prepared a set of "guided" backing tracks where I spell out the chord while they are playing. Once you have learned the chord progression by heart you can use the "plain" version. You can download them along with detailed explanations on how to use them by clicking here.

As strange as it may seem, this is one of the main factors in making your improvisations sound like music. If you are just playing for yourself you have nobody to communicate with, so your music does not sound genuine. If you are playing to impress other musicians, as often happens in a jam session, your music will sound artificial. But if you are playing in front of a public, then more often than not you are playing to tell them something, to establish a connection. You can gauge your improvisation by observing the reaction of the public, so the communication is two-way.

I know some players (and I am among them) whose improvisations are mildly boring when they are alone (for instance, while they are recording in their studio), but when in front of a real public they become able to deliver good solos. This is because they are focusing on communicating with the public rather than being self-centered on their technical ability.

Now, before you think "I will never be able to step on a stage", let me specify that with "public" I do not necessarily mean 10.000 paying people in a stadium. Two or three of your friends is enough public to get this started: ask them and they will be happy to listen to you. Again, do not wait to be good to do this otherwise you may never become good.

This is probably the more "esoteric" point I am making here, but it is the definite factor that makes your improvisation jump from "very good" to "mind-blowing awesome". This is, if you think about it, the whole reason why we are playing an instrument. Just stop for a moment now and think to the last song you listened today before reading this (or the song you are listening to right now). Does this song have a meaning or an underlying emotion? Of course it has one. What is the meaning of that song? I am sure that it is not difficult for you to answer this question, after all we all listen to music because it give us emotions or it tells us stories.

It is essential that your playing should tell something, or have an underlying feeling or emotion to it, yet very few people actually practice this. Wait a moment, did I just say you should practice emotions? Yes, I did utter such a blasphemy. And here is how we are going to do it.

Take your guitar, and using only three notes, try to express the deepest sadness you can. What notes are you using? How are you playing them? You have only three notes, you better choose and play them well! Now, do the same trying to express a calm serenity. Then try to express anger. Then express regret. Joy. Trepidation. Impatience. Boredom. Wittiness. Tiredness. Humor. Amusement. All of them using only three notes.

Make a list of other emotions you want to express. If you can't find a word for that emotion, describe a situation that gives you this emotion ("Summer afternoon reading a book under the shadow of a tree", "driving a fast car", "running the last mile of a marathon", etc), then try to express it using only three notes. Notice that there is not one right answer, rather there are many. With all the answers you collect from a single emotion, you can compose a solo.

Some of these points may apply to your situation, and some of them may not. You may need to work on the technical side of things (like the chord notes, or your phrasing) or you may need to work on your self-expression. I hope you have found here something useful for you. Take what you need and discard the rest. Stop playing notes and start playing music!

Tommaso Zillio is a professional prog rock/metal guitarist and composer based in Edmonton, AB, Canada.

Tommaso is currently working on an instrumental CD, and an instructional series on fretboard visualization and exotic scales. He is your go-to guy for any and all music theory-related questions.